If I had my druthers, if I could close my eyes and spin three times and land on the precise right spot, I'd find myself in Jerusalem, Nablus, Ramallah and Bethlehem--the occupied West Bank--for the Palestine Festival of Literature. PalFest 2010 gets under way on Saturday, May 1.

If I had my druthers, if I could close my eyes and spin three times and land on the precise right spot, I'd find myself in Jerusalem, Nablus, Ramallah and Bethlehem--the occupied West Bank--for the Palestine Festival of Literature. PalFest 2010 gets under way on Saturday, May 1.Last year the Israeli occupying army shut down the festival, or tried, unsuccessfully, for participants simply moved to another venue and carried on. This year festival organizers are no doubt prepared for anything as they "assert the power of culture over the culture of power."

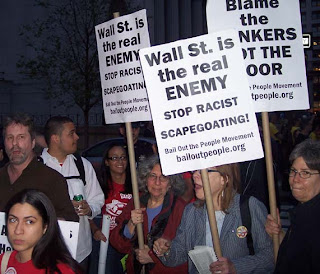

Of course I can't be there. But there's a mighty good place to be here on May 1. I refer, naturally, to the May Day March for Worker and Immigrant Rights, an action that has taken on added

urgency in light of the fascistic anti-immigrant law newly enacted in Arizona. I hope everyone who possibly can joins us in rallying and marching for multinational unity against the racist terror. If you're in the New York area, come to Union Square at 12 noon. There are similar rallies taking place in most major cities, so please find your way there too. There is after all a time for reading and writing, and a time to put on our marching shoes. May Day is for marching.

urgency in light of the fascistic anti-immigrant law newly enacted in Arizona. I hope everyone who possibly can joins us in rallying and marching for multinational unity against the racist terror. If you're in the New York area, come to Union Square at 12 noon. There are similar rallies taking place in most major cities, so please find your way there too. There is after all a time for reading and writing, and a time to put on our marching shoes. May Day is for marching.First, though, tomorrow night, if I can push myself, I'm planning to go hear the climatologist Dr. James Hansen along with environmental journalist Heather Rogers whose new book Green Gone Wrong: How Our Economy Is Undermining the Environmental Revolution might be worth a read. Neither is a revolutionary or advocates revolutionary action on climate change, although both as I understand it do see how extremely urgent the crisis is, so I'll be interested to hear how they confront this contradiction if indeed they do.

So that's what I wish I were doing and what I will be doing in the coming days. What I won't be doing is rush to the blah-fest currently taking place here in New York, the annual floating-in-cash-and-expensive-as-crap bloat known as the PEN World Voices Festival. Let me back up, because I didn't mean to sound that snide. I just leafed through this year's program, and look, it's not horrid. In fact there are some worthy offerings, including new work by Arab playwrights, a talk by Sherman Alexie on "the artistic, political and economic responsibilities of writers in the digital age," etc. It's not that it's monochrome, either, for it does includes some writers of color and from a number of countries. It's just that, on balance, it does not in fact offer anything close to what its title advertises: the voices of the world. Which would be the voices of workers and the oppressed. PEN is a construct of the bourgeois literary establishment devoted to promoting bourgeois literary values. It will never provide a platform for a revolutionary literary voice; in fact it often propagandizes against such voices, for instance those in Cuba. So while the glit-lit crowd wines, dines and opines, let's the rest of us march -- and write -- and organize -- in solidarity with the real world's voices, especially those of our sisters and brothers in Arizona. On May Day 2010.