Looking at literature through class-struggle lenses. Ruminations and rants on books, reading and writing from Shelley Ettinger, author of Vera's Will.

Tuesday, March 30, 2010

Linking along

Arundhati Roy on "Walking with Comrades" in the Dandakaranya Forests of central India. This is a long essay and I haven't had a chance to read it yet, but everyone keeps forwarding it to me with high praise so I thought I'd pass along the link.

The days of e-reader accessibility are coming closer. A new, cheaper, more usable one, the Kobo, is about to be marketed.

This enrages me. For obvious reasons, but also because we've been trying to work up a plan to visit the site, possibly during my summer days off.

Ricky Martin comes out. And yes, you're right that it took him long enough and yes we homos were wearied by his long closeting, but I also find myself wearied by self-righteous straight people who scoff as if coming out is now oh so easy.

Today is the second annual Global Day of Action for BDS--the movement for a Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions against the apartheid state of Israel in support of the Palestinian struggle. Join the BDS movement. Check out what people inside the Zionist entity, Jews as well as Palestinians, are doing to build the BDS call.

Finally, and most important, one more for Women's History Month: Sukant Chandan interviews Palestinian revolutionaries Leila Khaled and Shireen Said.

Monday, March 29, 2010

Making revolutionary art is not a crime

In 1966, at a mass rally attended by tens of thousands of workers in Beijing, Jiang Qing said:

To weed through the old to let the new emerge means to develop new content which meets the needs of the masses and popular national forms loved by the people. As far as content is concerned, it is in many cases out of the question to weed through the old to let the new emerge. How can we critically assimilate ghosts, gods and religion? I hold it is impossible, because we are atheists and Communists. We do not believe in ghosts and gods at all. Again, for instance, the feudal moral precepts of the landlord class and the moral precepts of the bourgeoisie, which they considered to be indisputable, were used to oppress and exploit the people. Can we critically assimilate things which were used to oppress and exploit the people? I hold it is impossible, because ours is a country of the dictatorship of the proletariat. We want to build socialism. Our economic base is public ownership. We firmly oppose the system of private ownership whereby people are oppressed and explotied. To sweep away all remnants of the system of exploitation and the old ideas, culture, customs and habits of all the exploiting classes is an important aspect of our great proletarian cultural revolution.At her 1980 "trial" at the hands of the "market socialism" grouping that had wrested control in China after the death of Mao Zedong, Comrade Jiang Qing proclaimed, "Making revolution is not a crime."

Neither is making revolutionary art.

Jiang Qing: Live like her! Long live the spirit of proletarian culture that she embodied, fought and died for.

Thursday, March 25, 2010

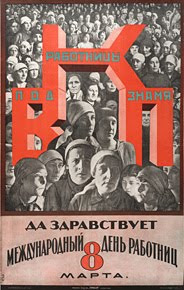

Women's History Month

There's nothing small scale about the participation of women in the great revolutionary struggle now under way in Nepal. They are playing a leading role.

These photos, courtesy of Jed Brandt, are from earlier this month, the International Women's Day march and rally in Kathmandu, Nepal.

These photos, courtesy of Jed Brandt, are from earlier this month, the International Women's Day march and rally in Kathmandu, Nepal. What a wonderful day that looks to have been.

What a wonderful day that looks to have been.Wednesday, March 24, 2010

Back soon, till then a little limn

Until then, check this out. A cogent, angry comment from Joy Castro on the character and consciousness of the literary powers that be.

And this. I haven't yet followed through on plans to feature excerpts here from the great new anthology Liberation Lit. I do still plan to do so, although it may be not in as systematic a way as I'd like. For now, consider this, to whet your appetite. It's from the long essay "Fiction Gutted: The Establishment and the Novel" by Liberation Lit co-editor Tony Christini. This is from page 575.

Misrepresentation 14--pre-eminence of the "subtle": "Subtlety of analysis is what's important," says [James] Wood. Not striking analysis, subtlety, which is another word for nuance--the establishment's all-time favorite word for the truncated range of its preferred fiction. Nuance is even more cherished than "limn." Subtlety--that by which never have so many nuanced so much to limn toward so little. Wood portrays the novel as sort of subtle styled character sketches of great sensitivity--a basic misrepresentation of the nature and scope of fiction, imaginative literature in full.

Friday, March 19, 2010

Seven years of imperialist war

First, tomorrow, comes the protest against seven long years of the criminal, murderous profiteering wars and occupations in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Next, on Sunday, the march for immigrant rights. There, the militant contingents will make clear that we're fighting for not just any "immigration reform," but full rights and legalization for all immigrants.

I'm sorry to say that I can't be in D.C., although I will be doing some political grunt work here in NYC so at least I'm not total dead weight this weekend.

Next up: May Day in New York City. All out in solidarity with immigrant workers! That one I know I won't miss.

Next up: May Day in New York City. All out in solidarity with immigrant workers! That one I know I won't miss.

Fela!

Wow.

Last night I made it back to Broadway for the first time in a year and a half. And for what a knockout of a show.

Fela!

This posting will be brief because my brain isn't doing its job of accessing words very well after staying up so late, and because I don't have much time to devote to it. Don't let brevity mislead you, however. Fela! is a night of musical theater like none other I've ever experienced. It merits a lengthy concatenation of superlatives leaping from the music to the musicians to the singers to the choreography to the dancers to the set and lighting design to the story to the politics. All of it, every aspect of this triumphant production, knocked my socks off.

Fela! is based on the life and career of the Nigerian composer/musician/singer/activist Fela Anikulapo Kuti, who in the 1970s created the Afrobeat music movement and went on to become a major force in the Pan-Africanist left. His mother Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti was a leader in the struggle against British colonialism and also in the women's movement. The musical depicts all of this--Fela's music, politics, and his mother's role and influence on the nation and on him--with great passion and equally great artistry.

I am now officially in awe of Bill T. Jones. I've long admired his work as a choreographer and dancer. He not only choreographed--and brilliantly, including, Read Red friends, a dance number having to do with books and reading, the dancers brandishing books as political weapons--but also wrote and directed this show. What an achievement. What a contribution.

Wednesday, March 17, 2010

Oh great

One visit and, damn it all, I'm hooked.

Curse you, Meredith Sue Willis, for turning me on to the live hummingbird webcam! Though I do appreciate your thoughts on how watching it is and isn't like reading.

Two boys & the Easter Rising

It stayed with me. O what a wonderful book can do.

It stayed with me. O what a wonderful book can do.To boil it down, which does this big book a definite injustice, it is the story of two teenaged boys in Dublin who fall in love at the same time they are swept up into the Irish republican struggle that culminates in the great Easter Rising of 1916. The two aspects of the book--tender heartbreaking love story and stirring portrayal of actual political-historical events--blend beautifully in just the way I wish more novelists would attempt. The scenes in which O'Neill depicts the main characters actually going through the events of the Easter Rising, moment by moment, are stunningly brought to life. All the passion, confusion, violence, rage and hope of the living struggle are there on the page. As are, equally, achingly, all the many dimensions of the boys' emerging love as they come of age and grapple with their gay identity amid their nation's great battles for independence from British colonialism.

This is also a novel of the highest literary achievement. The language throughout is stunningly grand, original, challenging, astounding. You open it and are at once whipped aloft as if by a whirlwind and there you stay, swirling about in the nether regions, the glorious heavens of grand innovation married to meaningful content, until you get to the last page and return to earth. Where you just might find yourself sitting and sobbing for a good hour or so, be warned.

When I read At Swim, Two Boys eight years ago, I was so enthused that I dug around and located the author's email address, then sent him a gushing fan letter. He was incredibly gracious in reply, writing a substantive, thoughtful and encouraging response. The next month he came to this country on book tour and I went to a reading where he signed my copy and we shared a brief but heartfelt conversation. I've held on to my feelings for his book and him ever since, along with a fantasy about asking him for a blurb if I ever manage to get my own novel published. Most of all, though, I cling to this brilliant, beautiful novel as a evidence of what literature can and ought to do.

For the valiant liberation soldiers who "bore their fight that the freedom's light might shine through the foggy dew," here is a tribute from the Wolfe Tones.

Tuesday, March 16, 2010

Rejection season

These were my three attempts to cadge the means for the optimal writing situation during my vacation days this coming summer. The optimal writing situation being two or three weeks in some quiet, pretty place outside the city. I've been dreaming of a sojourn at one of the arts colonies. Courtesy of rich donors, the colony houses and feeds you and provides everything you need to forget about everything you deal with during your regular workaday life so your mind can just sort of waft off into the ether and the words emerge. There's nature! Birds, trees! A swimming pool, even, at Yaddo!

I've been to three previous residencies and at each I became practically a different writer: enormously, uncharacteristically productive. I wrote a big chunk of my first novel at the first. At the second I completed the final rewrite. And at the third, two summers ago, I began my second novel, writing 65 pages of what I first thought was dreck and have since discovered is a pretty decent start to the story. None of these stays was at a place nearly as fancy-shmancy as Yaddo or MacDowell. I knew I'd have scant chance at the big time, but I decided to try this time around. I knew right, it seems.

As for NYFA, that's simply a piece of cash. I've applied many times before and I know, as with the arts colonies, that there's little likelihood of hitting the jackpot. If I did, though, I'd use some of it to create my own little writer's retreat. A cabin on Lake George is what I fantasize, just Teresa and me. In the morning I write while she reads or cooks or putters about, in the afternoon and evenings we vacate ...

Well. Anyway.

As it happens, I've recently sent out a new batch of submissions to literary journals so there's another bunch of rejection letters I can look forward to. I have mixed feelings about most of them (the journals, not my submissions ... well, okay, my submissions too). They are none of them the journal of my dreams, they are all of them pretty mainstream, they none of them partake of the class struggle, literary division. But they're what there is. They're where my stories might get read, should anyone accept any, and I have a humbly stubborn little feeling that a secretary's stories deserve to be read.

Does that sound pathetic? Nah, it shouldn't. For here I sit in my urban aerie and as I finish eating lunch and turn back to the work of entering data, filing the records, scheduling classes, helping students with their endless registration difficulties, I'm also watching out the window mesmerized by the buds on the tips of the winter-stripped tree branches as they begin to fuzz out into something like spring. It's that season too, or nearly. Rejection I can take, especially while I watch this promise peeking forth.

Sunday, March 14, 2010

Rainy weekend roaming

The Rainbow Book Fair is a couple weekends away, at CUNY's Center for Lesbian and Gay Studies. I should make myself go.

Amusing, via the Guardian: what it's like to spend a week without reading.

Yes, I'm a bit out of sorts three days into these howling rains. But I don't think that's why I found Jennifer Schuessler's piece "Take This Job and Write It" in today's New York Times Book Review tedious. Jeez, do they have a cycle on which they pull these tired, smarmily anti-working-class homilies out of the bin for yet another airing? It's as if there's a checklist to work through.

- Claim that few to no writers are actual workers: check

- Make fun of "proletarian novel" of the 1930s: check

- Dismiss all possible literary worth of working-class fiction: check

- Aver magical disappearance of production work (somehow, even though things keep being produced): check

- Assert that all labor has shifted to offices: check; and yet

- Dismiss office work as not real labor: check; but just to be sure

- Comment only on books "about work" that are actually only about management and administrative staffers in offices, not the vast majority of office employees who are wage workers doing data entry, clerical work, etc.: check

- Just in case you haven't made your case, come right out and announce that fiction that is about work is incapable of qualifying as literature: check

- Conclude with fatuous bourgeois-idological tautology about work and writing and writing about work: check

Friday, March 12, 2010

The Lacuna

Which is lukewarm. I didn't dislike this novel, although I do have some specific criticisms, which I'll get to presently. But I think that if this novel had been something more than it managed to be, the things I didn't like about it would have receded into the background. The book could have risen above its weaknesses and won me over. I understood for certain that it had not--not won me over, not taken me over the way I want a book to do--when I found myself, not 10 minutes after finishing The Lacuna, opening another novel and reading the blurbs and thinking ooh this looks good. Yeah, I know, famous last words, but that's not the point. The point is why was I able to immediately break the spell of the Kingsolver book and move on to the next? The reason, alas, is that there was no spell to break.

I've read most of Barbara Kingsolver's novels. I think the only one I haven't read is her last before this one, something about straight people having sex, icky icky icky, I just didn't feel like taking that trip. But in general I think she's a fine writer. She is certainly that rare creature in the world of mainstream U.S. arts and letters, an artist who tackles explicitly political topics. She deserves credit for that. Truth be told, though, I've never loved a book of hers. I've never felt transformed, transported. And so it is once again, this time with The Lacuna.

I don't think it's a question of style or structure. She has a lovely way with a sentence and the story flows smoothly for the most part. The problem, I think, is a lack of passion. A remove where what's wanted is a plunging in.

The story is told mostly in the first person, primarily via the journals and letters of the narrator and main character, Harrison Shepherd, born in 1915 in Virginia to a U.S. father and Mexican mother. Brought by his mother to Mexico as a child, he lives there except for a brief spell of boarding school in D.C., until he's a young man, when, in his 20s, he returns to the U.S. Here's the thing: this character is a cipher. There's very little life to him. He is all about observing and recording.

For a big chunk of the book--its middle section, its core, its heart--the story comes to life. Because what he's observing and recording, what he is in effect reporting to us, is the story of Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera, their households, their lives, work, art, politics. And for the best chunk of that, the heart of the heart of the book, our observer/recorder/reporter is there in the house in Mexico City during the time Leon Trotsky lives there in exile. In fact, Harrison becomes Trotsky's secretary. In fact, he's there when Trotsky is assassinated.

All of this is fascinating. And lovingly told. But it did not draw me in to the ostensible protagonist's orbit. He remains a device for the telling of the real story, which is about Kahlo and Rivera and Trotsky. This might not matter if that were all there were to the novel. But there is a considerable number of pages to get through before we enter this middle section, and again a fair piece of story, an important piece of story in fact, afterward in the last third of the book, especially the final pages when Harrison becomes a target of the McCarthyite witch hunt--and so it does matter that this character never comes fully alive, remains more or less a cipher, a device through which Kingsolver tells a larger story. That larger story is vitally important. I found it frustrating that I never cared very much about the character who's supposed to be living it, because he never came much to life.

I think this is because the character, as drawn, has no convictions of his own. He lives with some of the most important, vital persons of 20th century politics and arts; he gets caught up in the swirl of the signal issue of the 20th century, the class struggle as played out in the anti-communist frenzy of the McCarthy years--good heavens, what drama, what wonderfully meaty stuff Kingsolver holds in her hands here--and yet, steadfast, almost stubborn, throughout the book's 500-some pages he continues to merely observe, record, report. There's some awkward authorial effort to sort of explain this toward the end, to sort of tease out the mysteries of his personality, his reticence and so on, but it's too little too late, and in any case unconvincing, in my view. He's gay, that is made clear, but it is also kept nearly entirely off the page, with only the briefest, shyest, most glancing references; this annoyed and very nearly offended me, I mean, come on, author of a previous novel that focused on heterosex, don't give me some nonsense about the times, I know something about the times because of the research I did for my own novel, I just don't buy the near total skittishness, it feels like the author's rather than the character's, it feels inauthentic and unimaginative.

But the main fault I find with the main character's failure to engage, even more than this bizarre coyness regarding his gayness, is his remove from the grand political passions that are after all the real focus of the book. Kingsolver, via Harrison in his journals and so on, paints affectionate portraits of Trotsky and Kahlo in particular. It's a bit much to believe that he works closely with these two larger-than-life but real-life human beings whose lives were all about their beliefs political and artistic, that he cares for them deeply, that he takes dictation from and types articles and letters for Trotsky, for heaven's sake--and through it all, somehow, fails to be swept up himself in all this whirling vortex of ideas, of thought, belief, conviction.

What's going on here? Actually, I think it's more complex than Kingsolver's failure to imbue her protagonist with passion or conviction of his own. In a way, I think, she had no choice but to draw him this way, because otherwise her portrayal of Trotsky wouldn't work. Her portrayal of Trotsky as a human being is delightful; he comes to life on the page in much the way I've always imagined him. Her portrayal of Trotsky the revolutionary, however, is deeply erroneous. The Trotsky of Kingsolver's imagination is more or less a social democrat. He is more or less in the camp of opposition to the Soviet Union as it existed in the Stalin years. This is Trotsky denatured, declawed, Trotsky Lite for left-liberal consumption. In fact Leon Trotsky was a roaring lion, leader of the Red Army, theorist of the permanent revolution, scourge of petty-bourgeois liberalism--and, most important, defender and supporter of the Soviet Union to the day he died. Trotsky never wrote off the USSR, never turned against it, never joined in the crude caricaturing of it as having gone down in some kind of "Stalinist counter-revolution." Yes, he struggled to the day he died to right (left) the course of events. But no--no--no--he never took the side of imperialism against the revolution.

In effect Kingsolver gives the impression that he did. She sucks the revolution right out of him. Imagine that! He comes off instead as a crinkly-eyed kindly old man of the sort who might be comfortable with the Moveon.org brand of liberal activism. Oy vey. From her de-Trotskying of Trotsky, then, it's a short, straight! and necessary line to a passionless, opinionless, nearly disembodied protagonist.

Well, it looks like I have in fact settled on an opinion as I talked myself through this. There is a hole in this novel. A frustrating blank where I'd wish to have found a raging roaring blaze.

This then, for me, is the lacuna.

Monday, March 8, 2010

On this International Women's Day

During a mass meeting at Cooper Union that had gone on too long and was too dominated by male union officials, she famously strode up to the stage and, in Yiddish, shouted, "Enough talk! It's time to walk! Strike! Strike! Strike!" (or words to that effect) and thus the great battle began. By the way, if you want to see a pretty good reproduction of that historic moment, check out the 1996 movie "I'm Not Rappaport" with Ossie Davis and Walter Matthau. It opens with this scene.

During a mass meeting at Cooper Union that had gone on too long and was too dominated by male union officials, she famously strode up to the stage and, in Yiddish, shouted, "Enough talk! It's time to walk! Strike! Strike! Strike!" (or words to that effect) and thus the great battle began. By the way, if you want to see a pretty good reproduction of that historic moment, check out the 1996 movie "I'm Not Rappaport" with Ossie Davis and Walter Matthau. It opens with this scene.

Friday, March 5, 2010

Wednesday, March 3, 2010

Thank-heavens-winter's-end-is-in-sight links

Tomorrow, March 4, is the National Day of Actions to Defend Education. Mobilizations should draw lots of students especially in California, where the battle to defend the state university system has been going on for several months, and New York City, where CUNY students are fighting to save working-class students' access to higher education. On both coasts and in many places in between, there will also be events demanding an end to the attacks on the public education system, on public-school funding, on teachers and teachers' unions, and on the essential right to a free, equal public education for all. Which has never existed in reality in this country, but now is under open assault from Washington on down.

Tomorrow, March 4, is the National Day of Actions to Defend Education. Mobilizations should draw lots of students especially in California, where the battle to defend the state university system has been going on for several months, and New York City, where CUNY students are fighting to save working-class students' access to higher education. On both coasts and in many places in between, there will also be events demanding an end to the attacks on the public education system, on public-school funding, on teachers and teachers' unions, and on the essential right to a free, equal public education for all. Which has never existed in reality in this country, but now is under open assault from Washington on down.The New York Times chief book reviewer, Michiko Kakutani, likes Lionel Shriver's new novel So Much for That because it's not didactic! and it shows the problems of the health-care system for "regular middle-class families"!!! Oh goody. Because a novel that forthrightly addressed the issue and, ye gods, how it affects the vast majority, the working class and oppressed, those who don't qualify, apparently, as "regular," well gee who would want to read a novel like that?